Unit 12: Reasoning About Loops

Learning Objectives

After this unit, students should:

- understand how assertions can be derived in a loop;

- understand how assertions can help us understand the behavior of a loop;

- understand what is a loop invariant;

- be able to argue why a given loop invariant is true;

- be able to derive simple loop invariant of a given loop.

Using Assertions

We have seen how we can use assertions to reason about the state of our program at different points of execution for conditional if-else statements. We can apply the same techniques to loops. Take the simple program below:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

Before we continue, study this program and try to analyze what the function is counting and returning.

To do this more systematically, we can use assertions. Let's ask ourselves: what can be said about the variables x and y at Lines A, B, C? Let start with x first.

- Line A is the first line after entering the loop, so we can reason that, to enter the loop (the first time or subsequent times),

x > 0must be true. - We can also derive that, at Line A,

x <= n. This is less obvious: since we initialize thexton, and after Line A, we only decreasex,xcan never be more thann. - At Line B, we decrease

xby 1, so nowx >= 0 && x < nmust be true. - At Line C,

x % 5 == 0(i.e., x is multiple of 5) must also be true (since it is in the true block of theifblock). - At Line D, we already exit from the loop, and the only way to exit here is that

x > 0is false. So we know thatx <= 0.

Let's annotate the code with the assertions:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

What can be said about y? It should be clear now that we increment y for every value between 0 and n-1 (inclusive) that is a multiple of 5, based on the condition on Line C. That is, it is counting the number of multiple of 5s between 0 and n-1.

Loop Invariant

In the last unit, we say that there are five questions that we have to think about when designing loops. But we only talked about four at that time. The fifth question is: what is the loop invariant? A loop invariant is an assertion that is true before the loop, after each iteration of the loop, and after the loop. Thinking about the loop invariant is helpful to convince ourselves that a loop is correct, or to identify bugs in a loop.

Let's see an example of a loop invariant. Consider the example of calculating a factorial using a loop as before. To make the invariant simpler, let's tweak the loop slightly and start looping from i equals 1 up to n.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

Line A is where we want to identify the assertion before the loop; Line D is where we want to identify the assertion after each iteration of the loop. Line E is where we want to identify the assertion after the loop. We added Lines B and C to help us reason about the assertions at Line D.

For this function, the assertion at line A, D, and E are the same, they are all { product == i! }! Thus, we say that this loop has the invariant { product == i! }.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

Let's see why the assertions labeled above hold.

On Line A, the assertion is obvious. Since product is 1, i is 1, and 1! is 1. The assertion { product == i! } holds.

Let's look at Line B. We need to argue that this assertion holds for every iteration. This is a bit more tricky. Let's first consider the first iteration and come back to the subsequent iterations later. In the first iteration, the values of product and i do not change from Line A to Line B, so the assertion still holds.

On Line 11, we increment i. So, at Line C of the first iteration, we have { product == (i-1)! }.

On Line 13, we update product by multiplying it with i. So, we have on Line D of the first iteration that { product == i! } again.

Now, let's look at the second iteration. There is no change to the variables product and i, between Line D of the first iteration and Line B of the second iteration. So the assertion { product == i! } still holds. From this point onwards, we can apply the same argument over and over again, and see that the assertions on Lines B, C, and D hold for every iteration!

After we exit the loop, we can also assert that i == n, and so combining product == i! && i == n we have product == n!, which is what we want. The loop therefore correctly computes n!.

The approach above to argue that an invariant is true, can be generalized to the following steps. To argue that an invariant is true, we need to argue that:

- it is true before entering the loop.

- it is true at the end of the first iteration of the loop

- if it is true at the end of the \(k\)-th iteration of the loop, then it is true at the end of the \((k+1)\)-th iteration.

- it is true when we exit the loop.

The way we argue that an invariant is true above is similar to a mathematical proof technique called proof by induction. Induction is taught in CS1231. We will not require you to give a formal proof of invariant in CS1010, however.

When is an Invariant Useful

As we have seen in the example above, invariant is a useful thinking and reasoning tool to help us convince ourselves that our loop behaves correctly (e.g., { product == n! }).

Loop invariant, however, is not unique. We can write down possibly infinitely many loop invariant that is true. A good invariant, however, is one that will lead us to an assertion that we want to see (e.g., relating product to n). We can derive other invariants in our code (such as { n != 0 } below) that does not contribute to the resoning of the behavior of our loop. Such invariants should be avoided.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Problem Set 12

Problem 12.1

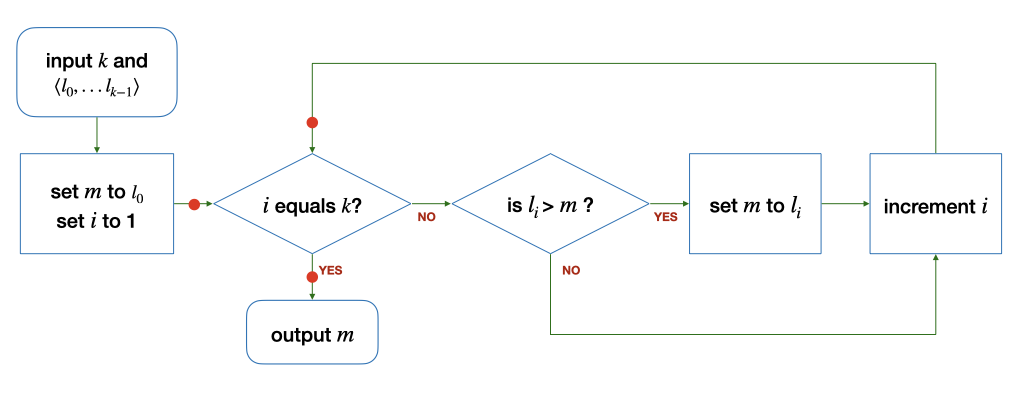

(a) Consider the algorithm to find the maximum among a list of integers \(L\) with at least one element (\(k > 0\)) below:

The loop invariant for this loop must hold at the three points marked with the red dots: before the loop, after each iteration of the loop, and after the loop.

State the loop invariant, explain why it holds at the three points above, and threfore argue that the loop above correctly finds the maximum among the elements of the list \(L\).

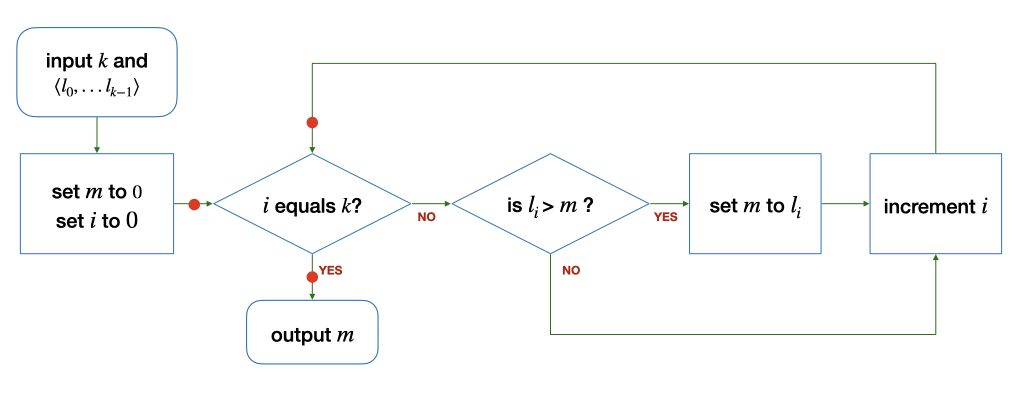

(b) Now, consider a slightly different algorithm to find the maximum among a list of integers \(L\) with at least one element (\(k > 0\)) below:

Explain why you cannot find a loop invariant similar to Part (a) above, and therefore show that the algorithm does not correctly find the maximum in certain cases.